forum

library

tutorial

contact

Solar Lamb-scaping: Solar Grazing:

A New Approach to Balancing Ag, Energy

by Berit Thorson

Capital Press, August 1, 2024

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Solar Lamb-scaping: Solar Grazing:

by Berit Thorson

|

"There is, in my opinion, no need to stop farming under solar panels ever.

And if you do, it's a lack of imagination."

-- Chad Higgins, associate professor, Oregon State University

MORROW COUNTY, Ore. -- Cameron Krebs maintains the grass on a 1,200-acre solar farm with help from thousands of autonomous lawnmowers.

MORROW COUNTY, Ore. -- Cameron Krebs maintains the grass on a 1,200-acre solar farm with help from thousands of autonomous lawnmowers.

Krebs, a sheep rancher in Morrow County, Ore., worked with Avangrid, a renewable energy business, to graze about 2,500 of his sheep around two large-scale utility solar farms from March through June.

The technique, called solar grazing, is a form of agrivoltaics, which combines agricultural practices with harvesting solar energy in the same location.

Essentially, Krebs has thousands of miniature mowers working as landscapers at the Pachwaywit Fields in Gilliam County, rather than Avangrid paying employees to mow and navigate heavy machinery around panels.

Agrivoltaics can come in a few forms, but the main ways are grazing and growing row crops beneath solar panels. Chad Higgins, an associate professor at Oregon State University, researches agrivoltaics.

"There is, in my opinion, no need to stop farming under solar panels ever," he said. "And if you do, it's a lack of imagination."

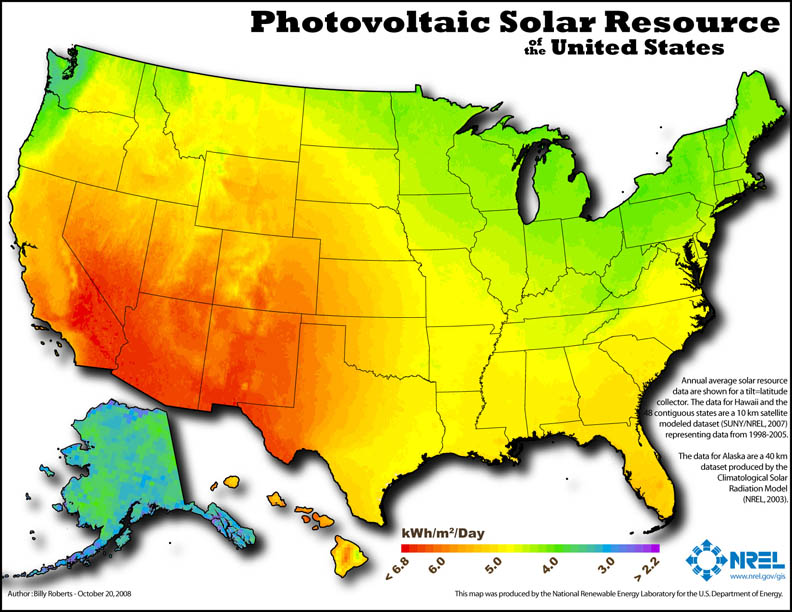

Solar panels need a lot of space, ideally in a flat, open area with plenty of sun, and deep soils that have been previously disturbed. Agricultural lands often fit that profile.

'A four-way win'

Oregon is home to numerous solar projects, with Avangrid's Pachwaywit Fields being the state's largest. It has a capacity of 211 megawatts, though some proposed sites would be bigger.

"There is a solar gold rush going on right now as the price of panels have decreased and as the regulatory and macro-structure has been more favorable," Higgins said.

Small, independent farms have tight financial margins, he said. But the one resource farmers and ranchers in Eastern Oregon often have too much of is the sun, Higgins said, since plants can't use all the sun reaching their leaves, meaning they "turn off" to avoid overheating.

"If you strategically take away the light plants can't use, that reduces the stress on the plants and they use substantially less water, so that frees up the water resource that's already tight," he said. "The plants grow (better) in the less stressed environment."

An agrivoltaic setup also helps the solar array produce more electricity. When solar panels overheat, as electronic devices in the sun tend to do, they produce less energy. The cooling effect from plants growing beneath the panels helps them produce more energy than they otherwise would.

"I call it a four-way win," Higgins said. "You have more food and better food with less water, and you also create more energy."

Establishing the agriculture-energy partnership

Agrivoltaics can't work for every crop in every scenario, Higgins said. With dryland wheat, for example, the combines used to harvest the crop are so big it would be hard to pair the machines with solar.

Still, if that issue is solved by autonomous tractors or harvesters, which are becoming increasingly accessible, wheat crops might partner well with solar.

For now, Northeastern Oregon might be better suited to Krebs' approach of having livestock graze on the grasses beneath solar panels. His partnership with Avangrid has prompted discussions about adjusting panels and seed mixtures to better accommodate grazing and promote a healthier landscape, said Krebs, who owns Krebs Solar Grazing.

"There's an overarching benefit to having a stable, biologically diverse ecosystem," he said.

Making decisions such as increasing the height of the panel might have higher upfront expenses, but the benefits are already clear.

Avangrid's senior solar manager, Dustin Ervin, said although the solar array wasn't built with sheep in mind, the sheep seemed to adapt to the site quickly and he expects it'll be even better with panel modifications.

Last year, the operations team was cutting grass for about 16 hours a day, which overwhelmed them, he said. The sheep alleviated that stressor. Plus, grazing helps prevent overgrown vegetation.

Still, at the outset, no one involved was sure how it would go. Ervin said they worried they'd end up with all their panels broken and wires chewed through, but that didn't happen.

Beau Davidson, site supervisor at Pachwaywit Fields, echoed Ervin. By the end of June 2024, he said, when vegetation is typically 4-6 feet tall, the grazed grass was 6-10 inches tall, which equated to a reduction of around 80% in the amount of fine fuel that could supply a wildfire.

While the main goal for Avangrid is to reduce combustibles on the site, solar grazing is a symbiotic relationship benefiting the land and sheep, too.

"Their droppings actually add to the fertilization of the ground, which is going to provide us better vegetation growth down the line, which will give them more tonnage to eat and a better palate for them to consider food," Davidson said.

And with better soil and vegetation management comes fewer unwanted weeds, which is better for farmers who own property close to the array.

A symbiotic relationship

The grazing also supports the local economy. Krebs, a fifth-generation livestock producer, lives just 13 miles from the solar site.

Krebs said he often thinks about different ways to use the sheep to graze in ways that benefit the animals and their environment.

"I think the correct way to manage vegetation is to use livestock and not herbicides and not diesel," he said. "So we can have this agrivoltaics combination where we have solar power generation, and we're also having food production and fiber production and supporting our economies."

Krebs's family also practices transhumance -- and has for more than 100 years, he said -- keeping the herds at low elevations in the winter and higher elevations in the summer.

Eastern Oregon has a unique growing season, Krebs said, and it's important to reduce combustible material before fire season starts. The transhumance approach for livestock management aligns with the solar site's needs before wildfires come.

"We've just continued to evolve and the new evolution today is solar production and then figuring out how things change, how do we maintain historical practices in the modern era," he said. "So it is taking shepherding or sheep herding and applying it to the 21st century that we're in and what resources are available, which is this vegetation under the solar panels."

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum