forum

library

tutorial

contact

Solar-Power Sharing Programs

May Be Poised to Take Off

by Cassandra Sweet

Wall Street Journal, September 13, 2015

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Solar-Power Sharing Programs

by Cassandra Sweet

|

Community solar projects offer those without rooftop panels a way to tap the sun's power.

Many consumers would like to switch to solar power but can't. It could be their homes have too much shade or their roofs can't accommodate solar panels, or perhaps they live in a condominium or apartment building.

Many consumers would like to switch to solar power but can't. It could be their homes have too much shade or their roofs can't accommodate solar panels, or perhaps they live in a condominium or apartment building.

Enter so-called community or shared solar, which allows people to buy solar power from centrally owned arrays. The power is delivered by the local utility, and customers get credits on their monthly bills for any power the project sells back to the grid.

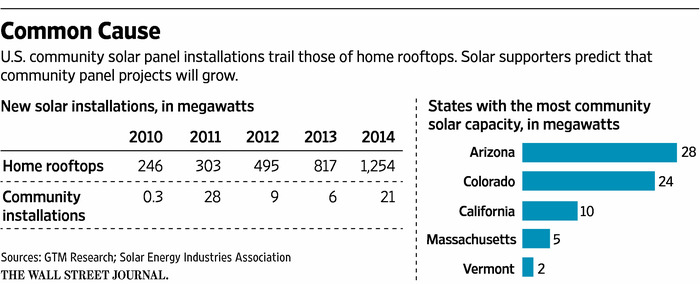

Although a relatively small business now, community solar is growing and could account for as much as half of the small-scale solar-panel market by 2020, according to an April forecast by the Energy Department's National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden, Colo. That would create a hefty new solar market in between individually owned rooftop arrays and large utility-scale projects.

"There's a lot of potential [for community solar], particularly with the cost of solar dropping every year and programs being put in place to make things easier and more affordable," says David Feldman, an analyst at the National Renewable Energy Lab and an author of the report.

Different approaches

The U.S. home solar-power market has grown rapidly in recent years, thanks to falling panel prices and government subsidies. Homeowners nationwide installed 918 megawatts of panels during the first half of this year, nearly quadruple the amount installed in all of 2010, according to GTM Research and the Solar Energy Industries Association. By the middle of 2015, there were about 4,400 megawatts of home rooftop solar panels installed in the U.S., according to GTM, compared with just 81 megawatts for community solar projects.

Community solar programs can vary widely by state and among utilities, partly because some states have rules for how regulated utilities must administer community solar programs and others don't.

In Colorado and Massachusetts, where such rules exist, participants make an upfront payment to buy a share of a solar-panel project, which is usually developed by an independent firm. The utility then buys power from the project and credits the participant for his or her share of the power.

Lower bills

Naomi Lederer, a librarian at Colorado State University, owns a 0.6% share of a 2,035-panel community solar project near her home in Fort Collins. She paid the developer $16,100 for her share and received a $4,500 rebate from her utility; she also expects a $4,800 federal tax refund after the array starts generating power this month. She expects her average monthly power bill to drop by 75%, and -- assuming electricity rates don't change -- she expects the investment to pay for itself in about 14 years.

"I love being green this way and not having to have the panels on my house," she says. If she has to move out of the area, she plans to sell her share to another resident.

Where there aren't statewide rules for community solar projects, utilities are experimenting with their own programs.

In Arizona, Tempe-based municipal utility Salt River Project built a 20-megawatt solar farm in Florence, Ariz., and offered the power to customers for 9.9 cents a kilowatt-hour; its typical residential rate is eight to 12.5 cents a kilowatt-hour. Nearly 2,800 residential customers and 96 schools signed up for the program, which locks in the rate for five to 10 years.

In California, the state's three big utilities -- owned by PG&E Corp., Edison International and Sempra Energy -- plan to sell solar power from community projects starting next year. The power will cost more, the utilities say, so they will emphasize the projects' green appeal instead.

Still, not everyone is a fan of community solar. In some states, utilities have to pay the same higher retail rate for community solar power that they pay homeowners with rooftop arrays. In contrast, they can buy power from large utility-scale solar-power plants at wholesale rates. The higher costs, utilities say, are a burden on nonsolar customers who pay for the programs through higher rates but don't see the benefits.

Xcel Energy Inc., which owns Minnesota's largest utility, is trying to limit the size of community solar projects in any one location to no more than five megawatts. It says power from community solar projects costs it roughly twice as much as the power from large solar farms. "We still have concerns about the cost," says Laura McCarten, a regional vice president at Xcel's Minnesota utility.

To address those concerns, some developers are seeking ways to build community solar projects that might benefit both utilities and customers. One idea is to build community solar arrays in areas where power is needed to even out the flow of electricity on the grid, which would allow utilities to avoid costly system upgrades.

"We're trying to strike some kind of balance" between utilities and consumers, says Paul Spencer, chief executive of Clean Energy Collective, which has worked with utilities to build community solar projects in Colorado and elsewhere.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum